Avogadro Number Analogies

Answer 1: The Avogadro’s number full is equal to 6.02214076 × 10 23. Furthermore, Avogadro’s number refers to the number of particles that exist in one mole of any substance. Moreover, this number is also known as the Avogadro’s constant and is the number of atoms that are found to be existing in exactly 12 grams of carbon-12. The numeric value of the Avogadro constant expressed in reciprocal mole, a dimensionless number, is called the Avogadro number, sometimes denoted N or N 0, which is thus the number of particles that are contained in one mole, exactly 6.022 140 76 × 10 23.

Avogado's Number is so large many students have trouble comprehending its size. Consequently, a small sidelight of chemistry instruction has developed for writing analogies to help express how large this number actually is.

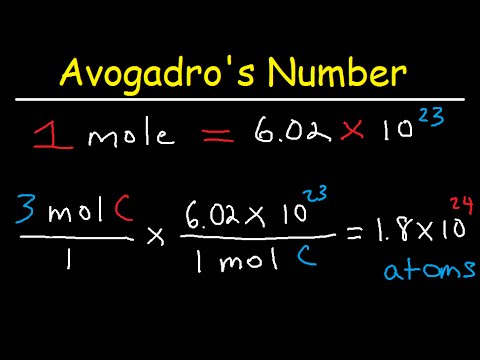

Before looking over the following examples, here's a nice YouTube video about the mole and Avogadro's Number. Have fun and please come back to the ChemTeam when you're done exploring.

1) Avogadro's Number compared to the Population of the Earth:

We will take the population of the earth to be six billion (6 x 109 people). We compare to Avogadro's Number like this:

6.022 x 1023 divided by 6 x 109 = approx. 1 x 1014

In other words, it would take about 100 trillion Earth populations to sum up to Avogadro's number.

If we were to take a value of 7 billion (approximate population in 2012), it would take about 86 trillion Earth populations to sum up to Avogadro's Number.

2) Avogadro's Number as a Balancing Act:

At the very moment of the Big Bang, you began putting H atoms on a balance and now, 19 billion years later, the balance has reached 1.008 grams. Since you know this to be Avogadro Number of atoms, you stop and decide to calculate how many atoms per second you had to have placed.

1.9 x 1010 yrs x 365.25 days/yr x 24 hrs/day x 3600 sec/hr = 6.0 x 1017 seconds to reach one mole6.022 x 1023 atoms/mole divided by 6.0 x 1017 seconds/mole = approx. 1 x 106 atoms/second

So, after placing one million H atoms on a balance every second for 19 billion years, you get Avogadro Number of H atoms (approximately).

3) Avogadro's Number in Outer Space:

If all the matter in the universe were spread evenly throughout the entire universe, there would be approx. 1 x 10¯6 nucleons per cm3. We could do several things with that. For example:

a) What volume (in cm3) of space would hold Avogadro Number of nucleons?6.022 x 1023 nucleons/mole divided by 1 x 10¯6 nucleons/cm3 = 6.022 x 1029 cm3/moleb) How many Earths would equal this volume of space (take Earth's radius to be 6380 km)?

4) Avogadro Number of Coins:

Take a common coin of your country and stack up 30 of them. Measure the height in cm and divide by 30. You now have the average height of one coin in centimeters.

a) How high in cm is a stack of Avogadro Number of that coin?

b) How many light years is this? (Light travels 3.00 x 108 km per second)

c) How many 'round-trips' is this to the moon? (Go there and back = one round-trip. The Earth-Moon distance (measured center-to-center is a bit more than 384,000 km.)

Another way to express this type of problem: If you placed one mole of pills (coins, etc.) with a diameter of 1.00 cm side by side, how many trips around the Sun's equator can you make?

Solution:

1) Convert diameter of Sun from km to cm:

(1.392 x 106 km x (105 cm / 1 km) = 1.392 x 1011 cmI looked up the diameter of the Sun online.

/what-is-a-mole-and-why-are-moles-used-602108-FINAL-CS-01-5b7583f6c9e77c00251d4d68.png) 2) Calculate circumference of sun:c = πd

2) Calculate circumference of sun:c = πdc = (3.14159) (1.392 x 1011 cm)

c = 4.3731 x 1011 cm

3) Calculate trips around the Sun:

Since each pill = 1.00 cm, one mole of them covers 6.022 x 1023 cm6.022 x 1023 cm / 4.3731 x 1011 cm

1.377 x 1012 times around the Sun.

5) Avogadro Number of Pieces of Paper:

If you had a mole of sheets of paper stacked on top of each other, how many round trips to the Moon could you make? (Hint: a stack of 100 sheets of ordinary printer paper is about 1.0 cm.)

6) The area of the ChemTeam's home state of California is 403932.8 km2. Suppose you had 6.022 x 1023 sheets of paper, each with dimensions 30 cm x 30 cm. (a) How many times could you cover California completely with paper? (b) Suppose each sheet of paper is 1 mm thick. How high would the paper be stacked?

7) If you drove 6.022 x1023 days at a speed of 100 km/h, how far would you travel?

8) If you spent 6.022 x 1023 dollars at an average rate of 1.00 dollar/s, how long in years would the money last? (Assume that every year has 365 days.)

Skills to Develop

Make sure you thoroughly understand the following essential ideas:

- Define Avogadro's number and explain why it is important to know.

- Define the mole. Be able to calculate the number of moles in a given mass of a substance, or the mass corresponding to a given number of moles.

- Define molecular weight, formula weight, and molar mass; explain how the latter differs from the first two.

- Be able to find the number of atoms or molecules in a given weight of a substance.

- Find the molar volume of a solid or liquid, given its density and molar mass.

- Explain how the molar volume of a metallic solid can lead to an estimate of atomic diameter.

The chemical changes we observe always involve discrete numbers of atoms that rearrange themselves into new configurations. These numbers are HUGE— far too large in magnitude for us to count or even visualize, but they are still numbers, and we need to have a way to deal with them. We also need a bridge between these numbers, which we are unable to measure directly, and the weights of substances, which we do measure and observe. The mole concept provides this bridge, and is central to all of quantitative chemistry.

Counting Atoms: Avogadro's Number

Owing to their tiny size, atoms and molecules cannot be counted by direct observation. But much as we do when 'counting' beans in a jar, we can estimate the number of particles in a sample of an element or compound if we have some idea of the volume occupied by each particle and the volume of the container. Once this has been done, we know the number of formula units (to use the most general term for any combination of atoms we wish to define) in any arbitrary weight of the substance. The number will of course depend both on the formula of the substance and on the weight of the sample. However, if we consider a weight of substance that is the same as its formula (molecular) weight expressed in grams, we have only one number to know: Avogadro's number.

Avogadro's number

Avogadro's number is known to ten significant digits:

[N_A = 6.022141527 times 10^{23}.]

However, you only need to know it to three significant figures:

[N_A approx 6.02 times 10^{23}. label{3.2.1}]

So (6.02 times 10^{23}) of what? Well, of anything you like: apples, stars in the sky, burritos. However, the only practical use for (N_A) is to have a more convenient way of expressing the huge numbers of the tiny particles such as atoms or molecules that we deal with in chemistry. Avogadro's number is a collective number, just like a dozen. Students can think of (6.02 times 10^{23}) as the 'chemist's dozen'.

Before getting into the use of Avogadro's number in problems, take a moment to convince yourself of the reasoning embodied in the following examples.

Example (PageIndex{1}): Mass ratio from atomic weights

The atomic weights of oxygen and carbon are 16.0 and 12.0 atomic mass units ((u)), respectively. How much heavier is the oxygen atom in relation to carbon?

Solution

Atomic weights represent the relative masses of different kinds of atoms. This means that the atom of oxygen has a mass that is

[dfrac{16, cancel{u}}{12, cancel{u}} = dfrac{4}{3} ≈ 1.33 nonumber]

as great as the mass of a carbon atom.

Example (PageIndex{2}): Mass of a single atom

The absolute mass of a carbon atom is 12.0 unified atomic mass units ((u)). How many grams will a single oxygen atom weigh?

Solution

The absolute mass of a carbon atom is 12.0 (u) or

[12,cancel{u} times dfrac{1.6605 times 10^{–24}, g}{1 ,cancel{u}} = 1.99 times 10^{–23} , g text{ (per carbon atom)} nonumber]

The mass of the oxygen atom will be 4/3 greater (from Example (PageIndex{1})):

[ left( dfrac{4}{3} right) 1.99 times 10^{–23} , g = 2.66 times 10^{–23} , g text{ (per oxygen atom)} nonumber]

Alternatively we can do the calculation directly like with carbon:

[16,cancel{u} times dfrac{1.6605 times 10^{–24}, g}{1 ,cancel{u}} = 2.66 times 10^{–23} , g text{ (per oxygen atom)} nonumber]

Example (PageIndex{3}): Relative masses from atomic weights

Suppose that we have (N) carbon atoms, where (N) is a number large enough to give us a pile of carbon atoms whose mass is 12.0 grams. How much would the same number, (N), of oxygen atoms weigh?

Solution

We use the results from Example (PageIndex{1}) again. The collection of (N) oxygen atoms would have a mass of

[dfrac{4}{3} times 12, g = 16.0, g. nonumber]

Exercise (PageIndex{1})

What is the numerical value of (N) in Example (PageIndex{3})?

Using the results of Examples (PageIndex{2}) and (PageIndex{3}).

[N times 1.99 times 10^{–23} , g text{ (per carbon atom)} = 12, g nonumber]

or

[N = dfrac{12, cancel{g}}{1.99 times 10^{–23} , cancel{g} text{ (per carbon atom)}} = 6.03 times 10^{23} text{atoms} nonumber ]

There are a lot of atoms in 12 g of carbon.

Things to understand about Avogadro's number

- It is a number, just as is 'dozen', and thus is dimensionless.

- It is a huge number, far greater in magnitude than we can visualize

- Its practical use is limited to counting tiny things like atoms, molecules, 'formula units', electrons, or photons.

- The value of NA can be known only to the precision that the number of atoms in a measurable weight of a substance can be estimated. Because large numbers of atoms cannot be counted directly, a variety of ingenious indirect measurements have been made involving such things as Brownian motion and X-ray scattering.

- The current value was determined by measuring the distances between the atoms of silicon in an ultrapure crystal of this element that was shaped into a perfect sphere. (The measurement was made by X-ray scattering.) When combined with the measured mass of this sphere, it yields Avogadro's number. However, there are two problems with this:

- The silicon sphere is an artifact, rather than being something that occurs in nature, and thus may not be perfectly reproducible.

- The standard of mass, the kilogram, is not precisely known, and its value appears to be changing. For these reasons, there are proposals to revise the definitions of both NA and the kilogram.

Moles and their Uses

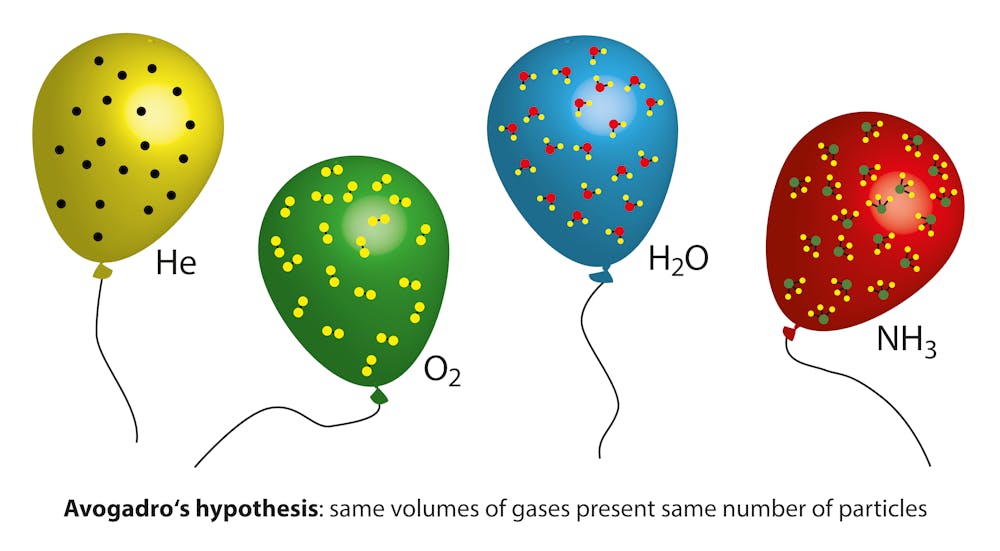

The mole (abbreviated mol) is the the SI measure of quantity of a 'chemical entity', which can be an atom, molecule, formula unit, electron or photon. One mole of anything is just Avogadro's number of that something. Or, if you think like a lawyer, you might prefer the official SI definition:

Definition: The Mole

The mole is the amount of substance of a system which contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 0.012 kilogram of carbon 12

Avogadro's number (Equation ref{3.2.1}) like any pure number, is dimensionless. However, it also defines the mole, so we can also express NA as 6.02 × 1023 mol–1; in this form, it is properly known as Avogadro's constant. This construction emphasizes the role of Avogadro's number as a conversion factor between number of moles and number of 'entities'.

Example (PageIndex{4}): number of moles in N particles

How many moles of nickel atoms are there in 80 nickel atoms?

Solution

[dfrac{80 ;atoms}{6.02 times 10^{23} ; atoms; mol^{-1}} = 1.33 times 10^{-22} mol nonumber]

Is this answer reasonable? Yes, because 80 is an extremely small fraction of (N_A).

Molar Mass

Md2all. The atomic weight, molecular weight, or formula weight of one mole of the fundamental units (atoms, molecules, or groups of atoms that correspond to the formula of a pure substance) is the ratio of its mass to 1/12 the mass of one mole of C12 atoms, and being a ratio, is dimensionless. But at the same time, this molar mass (as many now prefer to call it) is also the observable mass of one mole (NA) of the substance, so we frequently emphasize this by stating it explicitly as so many grams (or kilograms) per mole: g mol–1.

It is important always to bear in mind that the mole is a number and not a mass. But each individual particle has a mass of its own, so a mole of any specific substance will always correspond to a certain mass of that substance.

Example (PageIndex{5}): Boron content of borax

Borax is the common name of sodium tetraborate, (ce{Na2B4O7}).

- how many moles of boron are present in 20.0 g of borax?

- how many grams of boron are present in 20.0 g of borax?

Solution

The formula weight of (ce{Na2B4O7}) so the molecular weight is:

[(2 times 23.0) + (4 times 10.8) + (7 times 16.0) = 201.2 nonumber]

- 20 g of borax contains (20.0 g) ÷ (201 g mol–1) = 0.10 mol of borax, and thus 0.40 mol of B.

- 0.40 mol of boron has a mass of (0.40 mol) × (10.8 g mol–1) = 4.3 g.

Example (PageIndex{6}): Magnesium in chlorophyll

The plant photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll contains 2.68 percent magnesium by weight. How many atoms of Mg will there be in 1.00 g of chlorophyll?

Solution

Each gram of chlorophyll contains 0.0268 g of Mg, atomic weight 24.3.

- Number of moles in this weight of Mg: (.0268 g) / (24.2 g mol–1) = 0.00110 mol

- Number of atoms: (0.00110 mol) × (6.02E23 mol–1) = (6.64 times 10^{20})

Is this answer reasonable? (Always be suspicious of huge-number answers!) Yes, because we would expect to have huge numbers of atoms in any observable quantity of a substance.

Molar Volume

This is the volume occupied by one mole of a pure substance. Molar volume depends on the density of a substance and, like density, varies with temperature owing to thermal expansion, and also with the pressure. For solids and liquids, these variables ordinarily have little practical effect, so the values quoted for 1 atm pressure and 25°C are generally useful over a fairly wide range of conditions. This is definitely not the case with gases, whose molar volumes must be calculated for a specific temperature and pressure.

Example (PageIndex{7}): Molar Volume of a Liquid

Methanol, CH3OH, is a liquid having a density of 0.79 g per milliliter. Calculate the molar volume of methanol.

One Mole Avogadro's Number

Solution

Mole Avogadro's Number Worksheet

The molar volume will be the volume occupied by one molar mass (32 g) of the liquid. Expressing the density in liters instead of mL, we have

[V_M = dfrac{32; g; mol^{–1}}{790; g; L^{–1}}= 0.0405 ;L ;mol^{–1} nonumber]

The molar volume of a metallic element allows one to estimate the size of the atom. The idea is to mentally divide a piece of the metal into as many little cubic boxes as there are atoms, and then calculate the length of each box. Assuming that an atom sits in the center of each box and that each atom is in direct contact with its six neighbors (two along each dimension), this gives the diameter of the atom. The manner in which atoms pack together in actual metallic crystals is usually more complicated than this and it varies from metal to metal, so this calculation only provides an approximate value.

Vuescan reviews. Example (PageIndex{8}): Radius of a Strontium Atom

The density of metallic strontium is 2.60 g cm–3. Use this value to estimate the radius of the atom of Sr, whose atomic weight is 87.6.

Solution

The molar volume of Sr is:

[dfrac{87.6 ; g ; mol^{-1}}{2.60; g; cm^{-3}} = 33.7; cm^3; mol^{–1}]

The volume of each 'box' is'

[dfrac{33.7; cm^3 mol^{–1}} {6.02 times 10^{23}; mol^{–1}} = 5.48 times 10^{-23}; cm^3]

The side length of each box will be the cube root of this value, (3.79 times 10^{–8}; cm). The atomic radius will be half this value, or

[1.9 times 10^{–8}; cm = 1.9 times 10^{–10}; m = 190 pm]

Note: Your calculator probably has no cube root button, but you are expected to be able to find cube roots; you can usually use the xy button with y=0.333. You should also be able estimate the magnitude of this value for checking. The easiest way is to express the number so that the exponent is a multiple of 3. Take (54 times 10^{-24}), for example. Since 33=27 and 43 = 64, you know that the cube root of 55 will be between 3 and 4, so the cube root should be a bit less than 4 × 10–8.

So how good is our atomic radius? Standard tables give the atomic radius of strontium is in the range 192-220 pm.

Avogadro's Number Song

Contributors

Avogadro's Number Example

Stephen Lower, Professor Emeritus (Simon Fraser U.) Chem1 Virtual Textbook